Eswatini healthcare for a tourist

I wake up in a sweat, my pulse is racing and initially I don’t know where I am. Immediately the brain is wide awake, something is wrong. I know that as soon as I start to move, I will hurl. In the dark I start reaching for my things, where did I put my shoes and jacket? Eswatini in June is midwinter and freezing cold in the mornings (around 10 degrees celsius). I throw something on in a hurry, skip the shoes, I can’t wait. I rush out the dorm room, through the bar area, out towards the toilets. It is just after four AM, the fog is so thick the light can’t push through yet. Nobody is awake to witness my sprint to the toilets. I make it, thank goodness.

After that, my deterioration goes quickly. I can feel how my capacity to think diminishes by the minute. By eight o’clock I show no signs of improving and I start to feel scared. What on earth is going on? Food poisoning? How much can a person actually puke? I have no money on my phone to call my insurance, I’m stranded. Not great, I know, but in my defence I thought I would be leaving Eswatini this very day. By nine o’clock I manage to send my friend Tanya, who lives close by, an ‘SOS’ sms. No explanations nor context, just simply ‘sos’. As I open my eyes half passed out on my bed an hour later, I see her standing in my door. The sun behind her, lights her up making her look like a saint. This day, she certainly was.

My friend arranged for me to call my insurance company and once they had directed us to a hospital nearby, she made sure I got a driver for the day. I don’t remember much from the drive there, there was so much fog in my mind that every thought was an effort. The hospital I get taken to feels like something from a movie in the 1930’s. Everything is analog and slow, even the staff stroll as they work. I sit on the wooden bench and wait for my turn, it feels like I’ve slipped into a time bubble. I look at the dust that swirls around, caught in a stream of sunlight coming from the window. Finally, it is my turn. The Swazi doctor is warm and present. It calms me down to talk to him. He takes a look at me and then my papers. “Sorry mam, we don’t cover this insurance.”

My heart drops. I put my head in my hands. It is already two o’clock in the afternoon and my visa in Eswatini expires tomorrow. The hospital my insurance is now recommending me to go to is in another city. I am cold, my stomach is only still for 10 minutes at the time and I can barely think. The last thing I want to do right now is to take a bus to a city I don’t know. The doctor looks at me with empathy and says that he will call the insurance and see if they can sort something out.

The nurses come in and put me to bed, they give me the winter blanket to fight the cold. When I was still shivering twenty minutes later, they put another thick blanket on top of me. The hours pass by and I manage to doze off a little. When I wake up, I feel a lot better. My stomach had quieted and I could feel my brain coming back to life. The doctor comes back into my room and tells me I have to go to the other hospital first thing tomorrow morning. I nod and thank him profusely for all the care they didn’t have to give me but gave anyway. I paid nothing. I knew that the next morning, I would be on a bus to Maputo, Mozambique. The hospital would have to wait.

Crossing borders when sick

Travel guide: how to cross into Mozambique smoothly

Do not yell at the border police.

End of guide.

Border crossing into Mozambique

Looking back, it wasn’t my smartest decision to ignore the doctors orders to go to the hospital in Eswatini, but at the time I felt I had little choice. I could not obtain a visa for South Africa and every time I tried to enter Mozambique they gave me trouble. Eswatini was the only country which granted me visa and welcomed me with open arms, I did not want to screw up that relationship. Especially now that I was sick.

In order to make the trip from Ezulwini to Maputo, I decided to not eat or drink anything until I had arrived in Maputo. I didn’t want to risk a public explosion of the insides of my stomach. When I got to the Mozambican border they told me I was missing papers. I pulled them up online but the officers wouldn’t have it. It had to be printed and of course, theirs was out of function. With a deep sigh of resignation I turned around and started pulling my bags back to the Eswatini side where there was a printer.

When I get back to the Mozambican border, the officers say I am still missing a paper. At this point I am fully convinced that this is the famous Mozambican corruption in action, something I have become all too familiar with. I have a full melt down, yelling at the migration police everything that comes to mind. It is not a graceful scenario. Somewhere between an indignant rant about right and wrong, in fluent Portoñol (a mix of Spanish and Portuguese), it dawns on me that it doesn’t matter. Whatever they say is what goes.

I turn around on the spot and drag my bags back to the Eswatini side. When I finally get back to the Mozambican border I am parched. The sun is so hot and I haven’t had a sip of water in over 24 hours. The officers ignore me for 30 minutes before they decide that I have been humbled enough. “Have you calmed down now?” The lady behind the counter says condescendingly. “Have you?” I retort, looking her straight in the eyes. For what felt like minutes, we stood completely still, measuring each other with our eyes. Eventually, without a word, she processed my passport and sent me on my way. Sometimes I just want to bite my tongue off.

I arrived in Maputo after dark. They drop us in Baixa, downtown Maputo, a place I don’t want to be in at night, alone, with all of my belongings. I quickly ordered a taxi through Yango, their version of Uber, and thanked my lucky stars that I had money on my Mozambican sim card since the last time I was there.

On our drive to the Base Backpacker, one of two backpackers in all of Mozambique currently, I ask the driver to stop by a shop so I can get some water and chips. I realise, I know this city now. Or, I know this place well enough to be ill here. I could feel how I start to relax, in some ways, I felt like I was home. The next day, I went straight to the Lenmed Maputo private hospital, where all the rich people and foreigners go.

Solo Traveler’s Emergency Kit: Border crossing

– Have enough cash with you, preferably in dual currencies.

– Get yourself a local sim card and ensure you always have money on it.

– Keep your phone charged but ICE contacts printed on paper.

– Note insurance-approved hospitals before you go.

– Keep your insurance info accessible at all times.

– Print everything! (booking papers, incurrence, passport, etc)

Maputo healthcare for a tourist

The hospital is huge and it is unclear where the main reception is. Each hospital department seems to have its own front desk and no matter my best effort I cannot understand the cuing system. Finally, a lady behind one of the desks directs me to the right doctor’s office. I walked through a side door and turned to some staircases that made me feel like I was on my way to sneak in at some club. But that wasn’t the case. The doctors office was cool from the AC and the receptionist chewed gum loudly.

Despite having been in constant contact with my insurance company throughout this whole ordeal, when I arrived at the doctors, my insurance papers have the wrong date. The process of international health insurance was hard and I will not bore you with how extremely sorry I felt for myself, sitting at the Lenmed parking lot, recording all my sorrows in my video diary.

No, instead I will share two observations about the Maputo healthcare. Firstly, the bureaucracy of even the most prestigious hospital is still going to be SLOW. It took me the whole day to see the doctor and do half the tests and get all the papers in order. Another week to finish the rest of the tests. Then it took me another two weeks to actually get the results, and a few more days to see the doctor and get the actual prescription. Lucky I had four weeks of visa…

The second thing I observed was that the concept of patient privacy is not commonly practiced in Mozambique, at least not at this particular hospital. As I had my consultation with the doctor, nurses and staff kept popping their heads in and asking questions about other patients. When I was getting my insides scanned, the nurses who seemed to be on lunch break, came in to gossip with the doc. The Swede in me was absolutely horrified! But I was too exhausted to do anything, too hungry to ask them to leave, or at least ask them to lower their voices. They all seemed so casual about it so I decided it wasn’t worth getting embarrassed about.

Maputo rescue and recovery

After the first doctor’s appointment in Maputo I felt relief. Then came the exhaustion. My plan had been to spend the month in Tofo, a Mozambican seaside town in Inhambane. But after the journey I had into Mozambique, on top of not having eaten properly for weeks (apparently I had carried the bacteria for over a month), I felt an intense need to stay put. I hadn’t gotten my diagnosis and medication yet. Just the thought of moving out from the hostel today, only to do it again a week later in Tofo, only to have to return to Maputo and ultimately Eswatini again within twenty days, gave me anxiety.

On my third night back in Maputo, a friend took me out to dinner. He looked at me for a long while, we hadn’t seen each other in two months, since Bushfire. “Are you alright?” he asked. I started to cry. For a moment I was totally embarrassed by my emotional reaction, we didn’t know each other like that. He put his head to the side and in a brotherly fashion said “Talk to me.”So we talked.

He helped me organise a search for a room in the city. The relief I felt as soon as I had taken the decision to stay my whole visa in Maputo, was immense. Within an hour, I had replies from seven different people that I had met out and about during my first months in Mozambique. Nobody had anything right now but they all knew somebody who might have something. They all wanted to help. Right before we paid the bill, I had a showing for a room booked the very next day.

A new home in Maputo

I came to the showing the next day with all my bags in hand. I had already decided, this would have to work. I had met the father of the house quickly the night before, he lived smack in the middle of the city, on top of one of the infamous, ancient apartment buildings in Maputo. I cursed my inability to pack light as I pulled my luggage all ten stories up. As most older apartment buildings in central Maputo, it had running water sometimes. If you wanted a hot shower you had to boil the water. All laundry was done by hand and the electricity wiring could also be considered an adrenaline inducing, contemporary art installations.

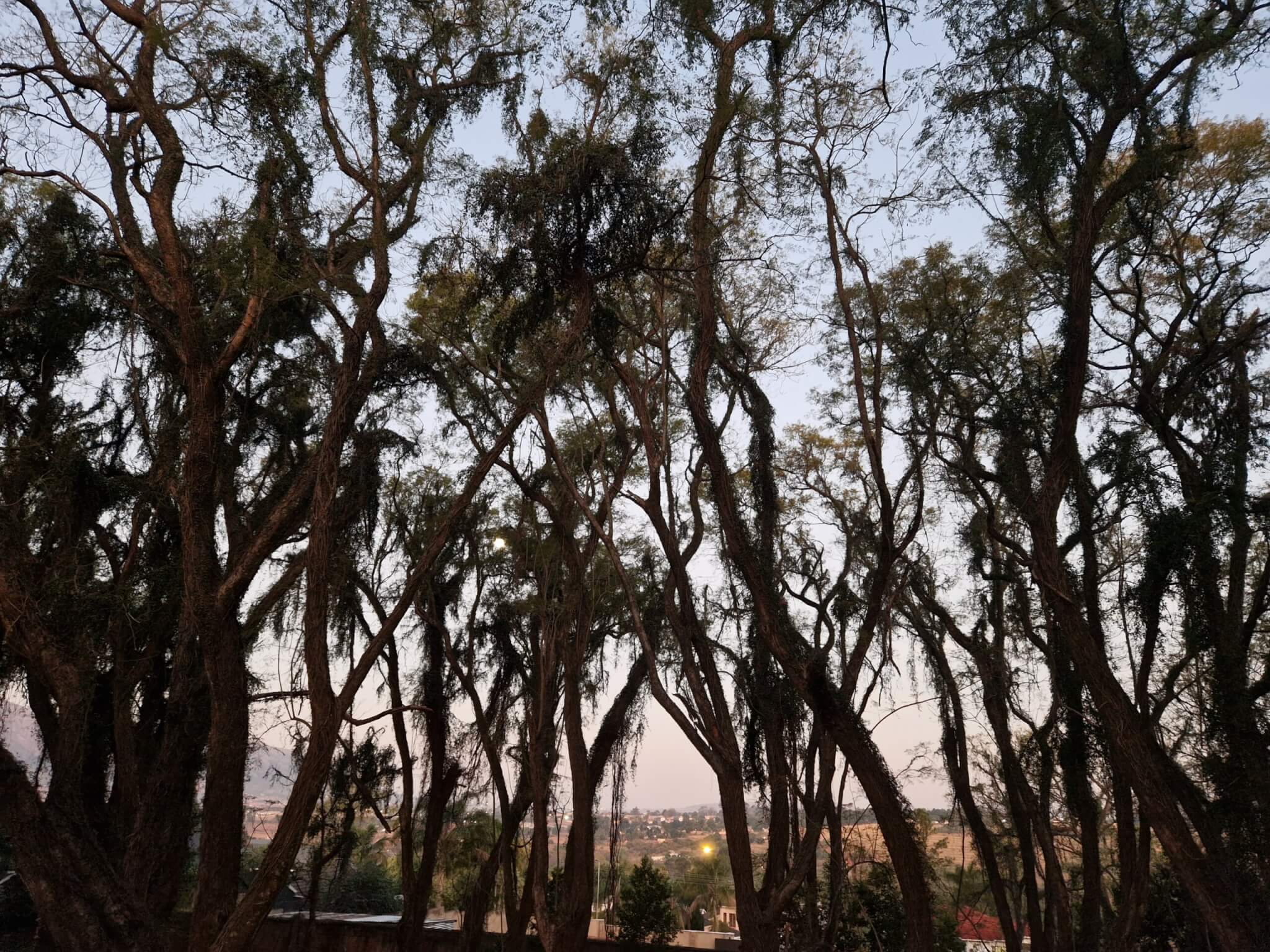

In this particular apartment there was no freezer and only one hot plate on the stove was working. Furthermore, there was no lock on the room and I had no fan. But the family felt kind and it was available immediately. When they showed me the rooftop, I felt that I had made the right choice. What a view! I have always been a sucker for roofs but this one took the price. To one side, the buildings and intricate life of Maputo spread out as far as I could see. To the other side, the horizon of the ocean framed Maputo’s skyline in a promise of pink light and foggy adventures. I could feel the beat of the city in what I could only describe as my hollow body. I needed rest.

The following weeks I practically lived on that rooftop. Some mornings I rose with the neighbouring mosque call to prayer. When it finished, I opened the gate to the rooftop and started moving. It wasn’t exercise-exercise, just small, silly movements. Not silly as in stupid but silly as in fun, as in making me actually smile and laugh. At this point, I knew three things 1) my body was super weak 2) I needed movement and 3) I needed joy in order to heal.

On that rooftop, with music pumping in my headphones I jumped and did cartwheels, danced and tried to learn to stand on my hands. Anything to get everything moving again. Slowly but surely I started to regain my appetite. It was a very still month for me. I reconnected with a few friends. I went to a beautiful event at Associação dos Músicos Moçambicanos . But mostly, I spent my time alternating between my bed, the kitchen and the rooftop. I could feel how not eating right had come to affect my whole nervous system. I was an emotional wreck.

The sustainable solo traveler

It seems to be a pretty common trait amongst long term, female travelers, to struggle with food. The traveling lifestyle doesn’t really allow for routine easily. Furthermore, changing contexts often, doesn’t give you a lot of known things to mirror yourself to. If change is the normal, how do you notice when some of the changes aren’t normal? It is so easy to be in adapt mode when you travel that you suddenly find yourself outside of yourself. I needed to take a serious look at what my needs as a person were. Movement; Joy; Time. And oatmeal. God knows I like my oats.

The whole getting sick thing shook me a little in my travel confidence. I had felt so bad! Been so vulnerable. Unable to think and process. My insurance was definitely not up to emergency standards, making me as a solo traveler, quite exposed. In that sense, slow traveling provides a bit of safety as it allows me to build a network of contacts to ask for help. But this time I only realised five-six weeks into being sick that I even was ill. If I would have traveled or lived with somebody, I think my diminishing appetite would have been noticed quicker.

Hence, going forward, I need context and community. How to get that as a solo traveler seems a bit contradictory but you never know. Either way, the thought of social sustainable traveling and tourism being sustainable for the traveler as well as for the place and people we are visiting, started to become more and more obvious. It became so obvious, I was embarrassed I had not made the connection before.

However, just because it was obvious, did not mean I knew what that meant in reality. How do I travel in a way so I am sustainable? When I returned to Eswatini a month later, I was still a bit shaky on my legs but my mission was clear: I had to find a different way to travel. A format adapted to me. I didn’t want to be limited to a maximum of 30 days, that was way too short for anything to grow! If the traveling lifestyle was going to be working for me, I needed to do some serious changes in how I travel. What are the biggest travel lessons you’ve learnt lately?

2 thoughts on “Health Emergency abroad: Solo Travel Strategies”

Hej Julia! Vilka strapatser, hoppas du mår bättre nu. Kramar

Jaa ibland blir det till att hålla hårt i hatten! Nu är magen i form igen. Kraam!